The World Finance 100 acknowledges the individuals and businesses that have looked past a year of turgid economic growth to keep pushing their industries forward

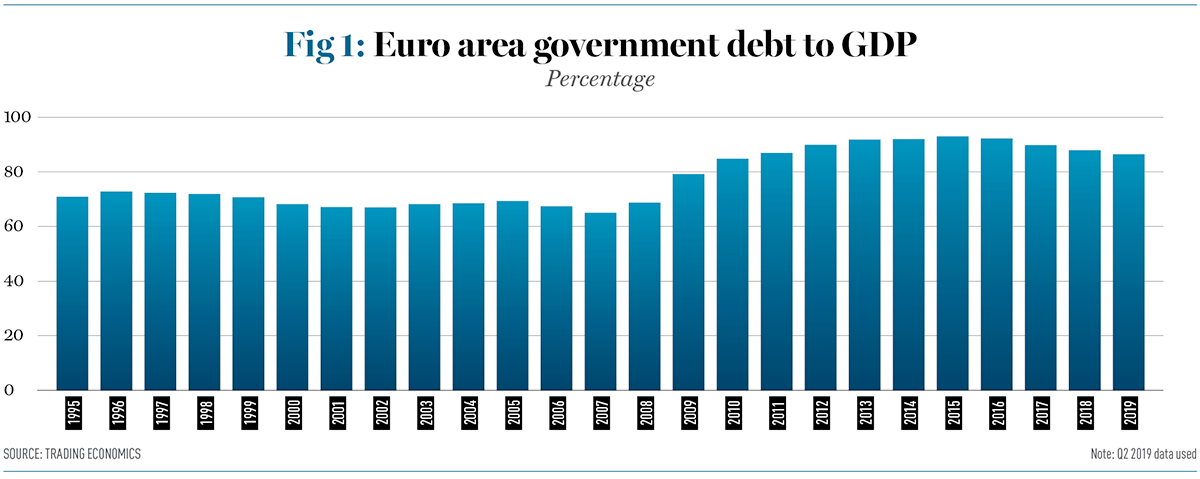

It’s difficult to know what to make of 2019 in terms of the global economy. There weren’t many disasters, but there wasn’t much to write home about either. This is perhaps most obvious in Europe, which experienced its seventh consecutive year of growth, but where debt remains high (see Fig 1) and future prospects are subdued.

The current stagnation places businesses in a predicament. They could invest now in an attempt to capture greater market share, or hold off in the hope that tomorrow will deliver a more supportive economic climate. Despite this uncertainty, some firms have pressed on, aware that standing still is rarely the right approach. The organisations acknowledged by the World Finance 100 have been recognised for their ability to lead their respective industries even in unfavourable conditions.

In the wars

Perhaps the biggest story of 2019 in terms of global finance was the ongoing trade dispute between the US and China. Many analysts have argued that the protectionist policies initiated by President Donald Trump – and the retaliatory measures launched by his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping – are in nobody’s best interests. But that hasn’t stopped them remaining in place.

While the statistics back up the assertion that the tariffs are causing substantial damage to global GDP, businesses have soldiered on regardless, recalibrating their supply chains to circumvent trade barriers where possible. With the cost of business rising, a survey by BizBuySell found that 64 percent of small business owners in the US have stated their intention to increase prices, while 65 percent are considering switching suppliers.

Aside from superpower posturing, conflict was present elsewhere in 2019. In September, a strike on two oil installations owned by Saudi Arabia was widely attributed to Iranian forces, ramping up tensions between the two Middle Eastern countries. The following month, two missiles reportedly hit an Iranian oil tanker. The attacks served as a reminder of the impact that political turmoil has in this part of the world and the consequences for the oil and gas sector.

Going back to China, ugly scenes continue to emerge from Hong Kong, after a dispute sparked by a new extradition treaty evolved into a broader struggle for the survival of democracy in the city-state. The unrest has caused much disruption to businesses situated in one of the world’s foremost financial centres. Recruitment has largely come to a standstill and companies that were originally set for expansion are beginning to reconsider their future in the Chinese territory.

Stuck in first gear

Although the world’s major economies successfully navigated 2019 without any major disasters, the year was far from inspiring. Slow growth was the order of the day throughout Europe, and while the US fared slightly better, fears are growing there too that trouble lies ahead.

In particular, economists seem at a loss over how to stimulate inflation. Interest rates and unemployment are low, the global financial crisis lies more than a decade in the past, but still inflation remains below central bank targets. It has led some analysts to suggest that ‘Japanification’ has spread to the West.

Since the 1990s, Japan has been trapped in a cycle of deflation and anaemic growth. Initially, economists blamed the Bank of Japan for not acting decisively enough when trouble arose. Now, a consensus is emerging that Japanification might simply be inevitable – and not only for its namesake country. Rapidly ageing populations, which must support fewer people of working age, lead to smaller economies and lower levels of growth. It’s a fate that Japan has been living with for 30 years, and it might become the new normal in Europe and the US as well.

“Persistently low interest rates give central banks little room for manoeuvre when the next economic downturn arises – a prospect that some experts are claiming could happen sooner rather than later”If Japanification does spread, it would likely increase the amount of negative-yielding debt, which would be welcomed by borrowers but not by long-term investors. Perhaps more worrying, persistently low interest rates give central banks little room for manoeuvre when the next economic downturn arises – a prospect that some experts are claiming could happen sooner rather than later.

The next recession is always a matter of when, not if. The US economy generally performed well throughout 2019, but there are fears that this was largely due to a $1.5trn tax cut at the end of 2017, which has provided a stimulus that is likely to fade over the course of 2020. Should that occur – and if the US does succumb to a recession – the impact will be felt far and wide. With an election on the horizon and economic uncertainty brewing, the global gaze is likely to remain fixed on the US for the foreseeable future.

End of an era

The close of 2019 brought with it the end of a difficult decade for businesses around the world. The 2010s will be remembered as a period that was dominated by the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Although many markets have now been stable for a number of years, growth has failed to reach pre-crisis levels. And while unemployment has reached record lows in many western states, job security appears to have been permanently damaged: in 2018, the share of eurozone workers deemed to be at risk of poverty reached 9.2 percent, up from 7.9 percent in 2007.

As ever, the economic picture in 2019 was not homogenous, and there were periods when some markets struggled and others thrived. In August, Greece finally emerged from the international bailout programme that had imposed a series of restrictions on the country since 2010. The news was greeted with muted celebration – while it meant Greece could return to international bond markets, limitations to public spending remained in place and some predictions suggest the country will still be paying off its current debt in 2060.

In the corporate world, the decade will be remembered for plenty of technological scaremongering – some of which was justified. Major corporations, from Facebook to Apple, faced scandal at one point or another – often related to their misuse of personal data. These are concerns that are unlikely to go away and are a reminder for all businesses, large and small, of their responsibility to their customers.

These responsibilities, however, will differ from country to country. The EU, which implemented its General Data Protection Regulation in 2018, has particularly stringent rules for digital firms to follow. China, on the other hand, boasts a very different political environment, with privacy policies that are more heavily weighted in the government’s – rather than the individual’s – favour. It is the responsibility of specific companies to make sure that they comply with the relevant legislation as it pertains to their particular industry and locale.

Just as businesses hope for a regulatory climate that is not overly restrictive, they will also be hoping that a new year – and, indeed, a new decade – brings more favourable economic conditions. The firms that have ploughed on during difficult times, continued to innovate and even flourished in spite of adverse conditions are those that have earned a place in the World Finance 100.

Congratulations to all those that made the final list.